At the annual meeting of the Menopause Society earlier this fall, researchers presented new evidence that hormone therapy can be beneficial to menopausal women’s heart health, reducing insulin resistance and other cardiovascular biomarkers. It was the latest in a long line of research showing the benefits of hormone therapy for women in menopause, which also includes alleviating symptoms like hot flashes, sleep disturbances, vaginal dryness, and pain during sex.

But despite this evidence, hormone therapy’s use has plummeted over the past few decades. In 1999, almost 27% of menopausal women in the U.S. used estrogen. By 2020, less than 5% did.

So why aren’t more women in menopause taking advantage of treatments known to be effective? Misconceptions about the risks of hormone therapy are one reason, according to experts. So is the lingering cultural taboo around discussing menopause, which has created “a perfect storm for under-treatment,” said Theodoros Kapetanakis, an OB-GYN at Mount Auburn Hospital’s Endometriosis Center in Waltham, Mass.

What we know about hormone treatment and cancer risk

The catalyst for the decline in hormone treatment for menopause was a 2002 landmark study called the Women’s Health Initiative that suggested the therapy came with an increased risk of heart disease and breast cancer. The study specifically focused on using both estrogen and progestin therapy among older, postmenopausal women, most of whom were not experiencing symptoms like hot flashes anymore. It was discontinued due to increased risk as compared to a placebo.

In the aftermath, both the media and policymakers construed the data as demonstrating a higher risk for menopausal women as well. In 2003, the Food and Drug Administration added a black box warning — the most stringent — to all products for menopausal women with estrogen alone or in combination with progestin.

But research has since shown that the risk of adverse events from hormone therapy is low for menopausal women (typically before age 60) looking to relieve their symptoms.

Assessing risk is more complicated for postmenopausal women. A 2020 JAMA paper offered a long-term follow-up on the Women’s Health Initiative trials. It found that prior use of estrogen alone was associated with a lower risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women who’d previously had hysterectomies. Postmenopausal women who still had their uteruses intact and who had taken progestin with estrogen did have a higher risk of breast cancer, though no difference in mortality rates.

More research presented at this year’s Menopause Society meeting found there’s no one-size-fits-all age limit on hormone therapy for the up to 15% of women in their 70s who still experience hot flashes. “Consideration must be given to their specific risk factors and health status,” Stephanie Faubion, medical director of the Menopause Society, said in a statement at the time.

But researchers and clinicians are still trying to spread the word about the newest research on hormone therapy.

“Women don’t always know that their symptoms are manageable outside of lifestyle changes,” said Faubion. “It takes a long time to undo thinking.”

The difference between systemic hormone therapy and local estrogen treatment

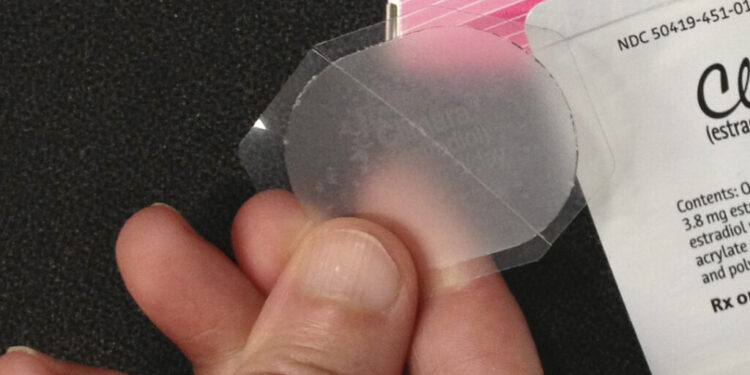

Part of the confusion for patients has to do with the many different types of hormone therapy that are available. Systemic hormone therapy — meaning a higher dose that is absorbed into a person’s bloodstream — is most commonly given through a patch or pill. It can help relieve the common menopause symptoms, as well as provide preventative benefits when it comes to osteoporosis.

Local or vaginal estrogen treatment, like a topical cream or ring, is a lower dose that can specifically target vaginal or urinary symptoms of menopause.

The same black box warning appears on local estrogen products as on systemic estrogen. But the risks are not nearly the same, even for older women who were represented in the 2002 study population, experts say.

When estrogen is given locally — say, as a topical cream — it’s a low dose that doesn’t get fully absorbed into the bloodstream as the systemic estrogen does.

Let’s Talk Menopause is an advocacy organization arguing for the FDA to drop the label from local hormone products.

“I tell my patients before they leave, ‘Just so you know, you’re going to get this black box label that says it can do all these horrible things. I promise you, it does not do that,’” said Robin Noble, an OB-GYN who often prescribes local estrogen, and chief medical advisor for the group.

The FDA rarely removes black box warnings. If it does, a surplus of evidence is needed. But experts say it would be extremely difficult to do research on menopause treatment at the same scale as the 2002 study, which was part of the national, long-term Women’s Health Initiative.

“It’s going to cost over $100 million,” Faubion said. “I think the desire to fund that kind of trial — that we would need to run for ten or more years — the appetite is low.”

An individual decision

Whether somebody going through menopause should take some sort of hormone therapy depends on both their symptoms and their personal philosophy on aging, said Noble. Maybe somebody wants to control classic symptoms like hot flashes. Another person could have aesthetic concerns, wanting to clear their skin or combat the weight redistribution that often happens during menopause. Or maybe they don’t have bad symptoms at all, but know they’re at risk for osteoporosis, which hormone therapy is known to reduce the risk of.

On the other hand, somebody may choose not to take hormones if they have a family history of blood clots or breast or cervical cancer. Or an individual might be particularly risk-averse, and doesn’t want to take any medication if they can help it. And of course, some lucky people just have mild symptoms and don’t feel any need for relief.

“Choice, philosophy, and informed decision-making really play a role. What is that individual’s goal?” Noble said.

Noble is one of a limited number of providers in Maine who are certified menopause practitioners through the North American Menopause Society (now the Menopause Society). Because of that, she often has a long waitlist of patients who want to see her. Rather than wait, some patients may go to a med spa for hormone treatment, where practitioners may not be well-trained to help patients figure out the best options. Several times a week, Noble says she sees patients who are “backing out of some crazy regimen” of hormones they started at a med spa or similar facility.

All physicians, but particularly primary care doctors, need to better understand menopause and how to treat its symptoms, Noble and others said. Because if doctors aren’t aware of the effectiveness and safety of hormones, it’s hard to expect their patients to be.

“Women are, I think, being bombarded with messages on both sides that leave them confused,” said Faubion. Advocates aren’t saying that everybody going through menopause should be on hormone treatment. But right now, almost nobody is on it. “The balance is somewhere in between.”

The bottom line, experts say: If you want it, or need it, there’s likely an option that works.