A study published Thursday contains a sobering piece of news about the H5N1 bird flu viruses circulating in cows in the United States: A single mutation in the hemagglutinin, the main protein on H5N1’s exterior, could turn a virus that is currently not well equipped to infect people into one that is much more capable of doing so.

Scientists from Scripps Research, in La Jolla, Calif., reported in the journal Science that one mutation in the hemagglutinin changed the type of cell receptors that the virus is best suited to attach to, switching its preference from those found in birds to those that abound in the human upper respiratory tract.

The authors termed their finding “a clear concern” — a view shared by other influenza scientists asked to review the paper by STAT. Debby van Riel, a virologist at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, suggested it could be that the version of the virus currently spreading in cows has a higher zoonotic potential — a greater capacity to jump species — than previous iterations of H5N1. But she and others, including the Scripps team themselves, cautioned that this one change on its own might not be enough to morph this virus into an efficient human pathogen.

While “the mutation to recognize human-type receptors is a crucial step, additional mutations are likely required for the virus to become fully transmissible between humans,” Yoshihiro Kawaoka, a flu virologist cross-appointed to the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the University of Tokyo, told STAT in an email. “Unfortunately, we don’t yet know what these additional mutations might be, as this area of research has not been extensively studied.”

Adding to the concern the findings are provoking is the fact that a mutation at the same position on the hemagglutinin that the group studied was recently seen in viruses taken from a teenager in British Columbia, Canada, who contracted H5N1 around the end of October and became seriously ill. The teenager has been in critical condition in a Vancouver hospital for several weeks. Authorities there have been unable to determine how the teen became infected.

The mutation in the Canadian teenager was at a position known as 226 on the hemagglutinin’s receptor binding site — the one the Scripps team found was critical to switching the receptor binding preference. But the amino acid changes in the teen’s virus were not identical to the ones shown by the Scripps team to alter the receptor binding preference. The mutation at position 226 was one of two important changes in the hemagglutinin seen in the virus from the teenager.

It’s not known if the mutation was in the virus that first infected the teenager, or if it developed in the teen during the course of the infection — though scientists suspect the latter. It appears, though, that the teenager — who is no longer infectious — did not pass the virus anyone else, so that mutated virus will have died out.

Scott Hensley, a professor of microbiology at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, described the finding that a single mutation could change the receptor binding preference of this version of H5N1 as “alarming” — especially in light of the Canadian case.

“I think there’s a chance — I’m not saying it would [have] happened, but I think there’s a chance that those two substitutions in that British Columbia case could have triggered a pandemic if there were enough people exposed to that virus,” Hensley said.

It’s long been assumed that H5N1 or any bird flu virus would need to switch its receptor binding preference in order to gain the capacity to spread easily among people — a development that would trigger a pandemic. This type of binding switch was seen in the 1918, 1957, 1968, and 2009 flu pandemics. But work conducted by the Scripps team on earlier versions of H5N1 suggested multiple mutations would be needed to achieve this end.

This time was different.

“It was quite difficult to change the receptor specificity previously of H5N1 viruses,” Ian Wilson, one of two senior authors of the paper, said in an interview. But when the group studied the hemagglutinin of a virus retrieved from the first confirmed human case in this outbreak, a dairy farmworker in Texas, “to our surprise, the single mutation … actually could change that receptor specificity.”

Wilson, who is a professor of structural biology at Scripps, called the fact that a mutation appeared at the same position in the virus in the British Columbia teen “striking.”

That three or more mutations were previously required to change the receptor binding preference of the virus set a high bar for the virus to scale. One mutation, though, changes the calculus, the paper noted. “Because each mutation is independent and the probability of achieving additional mutations decreases exponentially, our observation that a single mutation is sufficient to switch receptor specificity … dramatically increases the likelihood of achieving this phenotype required for human transmission,” the authors wrote.

That said, Wilson stressed that the team did not want to overemphasize their finding, saying their research cannot predict if the virus will make this change, or if this is the only way a change in receptor binding preference could occur.

“Clearly there have been H5N1 infections around for a long time and it hasn’t happened yet,” he said. “However, this virus is a little bit different from that.”

Research from van Riel and colleagues at Erasmus supports this idea. In a recent preprint (a paper that has not yet undergone peer review) they reported that a version of the virus from 2022 — from the same subset or clade as the virus now circulating in cows — attached more easily to cells from the human respiratory tract than an H5N1 virus that had circulated in 2005.

This version of the virus is known as clade 2.3.4.4b. To date this year, 58 people in the United States have been infected with this virus. (The teen in British Columbia was also infected with a 2.3.4.4b virus, though one that was slightly different from the one circulating in cows.) Most of the U.S. cases have worked on affected dairy farms or have been involved in culling infected poultry. None has suffered serious illness — a fact that Hensley worries has led the agricultural industry to dismiss the threat the virus poses.

Farmers in many parts of the country have resisted testing for the virus and there is a widespread belief that more farms and more states have had outbreaks than have reported them. As of Thursday, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has confirmed 718 herds in 15 states since the outbreak was first detected in late March.

“There’s this general idea among farmers and people in the government that this is not [a big deal] — why do anything?” Hensley said. “As we’ve seen in the British Columbia case, a single substitution or two or three substitutions can change that equation altogether. And all of a sudden, you can have a virus that’s much more pathogenic.”

Seema Lakdawala, an associate professor in the department of microbiology and immunology at Emory University School of Medicine, agreed.

“We as a country are not taking H5 seriously enough. Absolutely. This paper does not do any more to remind me [of that],” Lakdawala said. “But if it helps remind others that it’s important, great.”

She and others STAT spoke to about the study described the work as very good science.

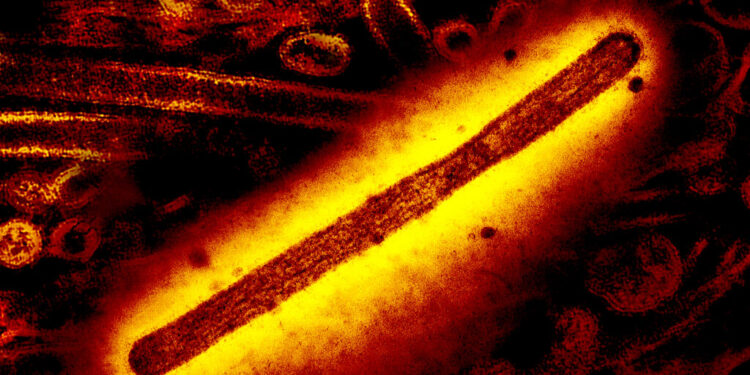

The Scripps team wanted to see what it might take for the hemagglutinin protein of this version of the virus to gain the capacity to easily attach to the cells in the human respiratory tract. So it looked at what might happen if mutations occurred at sites on the protein that are known to change the receptors to which the virus can attach.

Bird flu viruses attach to receptors known as alpha 2-3, which are plentiful in birds but are rare in human upper airways. In people, alpha 2-3 receptors are found mainly in the mucosal membrane around the eyes — most of the human cases in the U.S. have suffered from eye infections — and deep in the lungs. In the human upper airways, a type of receptor known as alpha 2-6 predominates. The mutation the Scripps team identified changed the binding preference from alpha 2-3 to alpha 2-6 receptors.

The work was done by studying the hemagglutinin of a virus that had infected the first confirmed human case in the U.S. this year, a farmworker in Texas who was presumed to have been infected by exposure to infected cows.

The team did not work with whole live viruses. Adding mutations to bird flu viruses that might increase their capacity to infect people is considered gain-of-function or enhanced potential pandemic pathogen research. This type of work cannot be conducted in the United States with federal research funding without prior approval from the National Institutes of Health.

Ron Fouchier, a virologist at Erasmus Medical Center who has studied H5N1 for more than two decades, suggested the Scripps paper should serve as a reminder of why allowing H5N1 to circulate unchecked in cows is dangerous.

“The manuscript … demonstrates that the American cow-origin H5 influenza viruses might acquire human receptor specificity easily, providing yet another reason for rapid eradication of this virus from the U.S. cow population,” he said in an email.

Lakdawala concurred. “Every single case, every single spillover, has the potential to adapt,” she said.