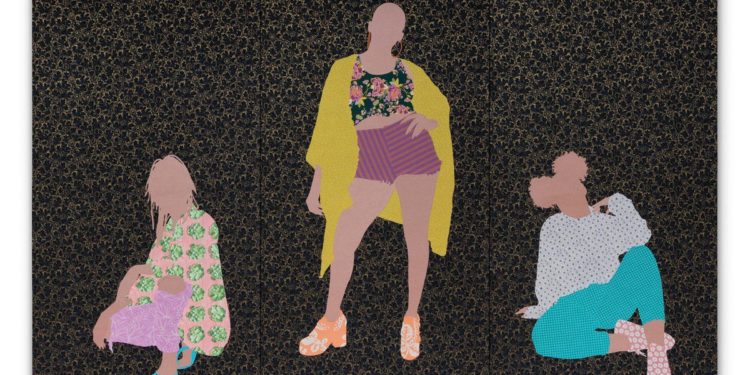

Gio Swaby, Gyalavantin’ , 2021, Thread and material sewn on canvas.

Courtesy of the Artist and Claire Oliver Gallery, New York.

“How lengthy did that take you?”

If artists had a greenback for each time they heard that query they’d have higher wealth than their collectors.

Every canvas, sculpture, basket, quilt, pot or drawing represents the end result of years of coaching, follow and life expertise, no matter whether or not the completed mission took weeks or minutes to finish. Gio Swaby (b. 1991; Nassau, Bahamas) exemplifies this.

Her delicate, richly nuanced portraits outcome not solely from a protracted follow of creative examine, however a deep dedication to her relationship with every sitter, the connection which permits her portraits to transcend mere bodily representations into insightful character research. In truth, Swaby considers the completed artwork piece merely a byproduct of the connection.

“For me, these bodily items usually are not essentially the work itself,” Swaby advised Nikole Hannah-Jones for an interview revealed in “Gio Swaby: Fresh Up,” the exhibition catalog accompanying Swaby’s first solo museum presentation of the identical title now on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg (FL). “The work is extra making connections and rising love. These portraits are like a dedication to that work, or a residue of that work.”

As everybody can attest to, relationships–profitable ones, lasting ones–require dedicated, selfless work to attain. It’s work Swaby appears to relish. It’s the work her progressive work take as their basis.

Swaby is aware of each certainly one of her sitters properly. She portrays her sisters and shut mates. Dialog serves a key position in reaching these portraits of magnificence and energy she calls “love letters to Black girls.” Her portraits start with a photograph shoot the place the artist and topic collaborate on a cohesive story advised by way of clothes and poses. Swaby foregrounds their private model—seen within the detailed renderings of bijou, hair and clothes—creating area for self-definition and unapologetic self-expression.

“I need to create portraits which might be stuffed with the essence of that individual and who they’re and be capable to try this in a means that’s delicate, that holds a lot respect and reverence and love for the individual being represented,” Swaby advised the MFA, St. Petersburg throughout an on-line preview of the present.

In so doing, mixed together with her distinctive vary of textile-based methods together with embroidery and appliqué constructed from an unbelievable array of colourful materials and complex freehand strains of thread on canvas, Swaby has discovered a contemporary and compelling means of creating a person mark on a style which has existed for thousands of years and been practiced by numerous artists. None like Swaby, nevertheless.

Portraits of such remarkably particular person creative conception and brilliance they make as a lot of a press release concerning the artist, because the sitter. They characterize a breakthrough artistically. They provide viewers a brand new means of seeing individuals, a brand new mind-set concerning the world.

Decolonizing Portraiture

Swaby’s artworks goal a higher function than celebrating her inside circle.

“A lot of the artwork we’ve seen of Black individuals, traditionally, has not been made by Black individuals. It exhibits a lot struggling and trauma, and I believe that seeing ourselves represented like that has a robust detrimental impact on our psychological and emotional well being as a result of we see a model of ourselves mirrored in these photos,” Swaby additional shared with Hannah-Jones within the exhibition catalog. “What I’m attempting to do is use my follow to fight these photos, to create representations which might be nuanced and keep the company of the sitter. My follow is an try to decolonize portraiture in a means that subverts, or typically outright rejects these photos that present us at our lowest moments.”

MFA, St. Petersburg’s presentation of greater than 40 Swaby portraits of completely Black girls stays startling in a museum context for its rarity. Forty portraits of white males–the Aristocracy, the rich, army and political leaders–and even 40 footage of white girls–more than likely nude, idealized, fawning, objectified–wouldn’t increase an eyebrow. In any case, that has been the inventory and commerce of artwork museums ever since there have been artwork museums.

However putting all these on a regular basis Black girls collectively, completely–honoring them, glorifying them–in a prestigious establishment not removed from its Greek and Roman antiquities and subsequent string of European wonderful artwork masterpieces, nonetheless feels groundbreaking. Virtually subversive.

What are they doing right here?

That impression speaks to the continued legacy of colonialism on museums. On tradition.

“If you find yourself a white one that grows up in a world the place the artwork world, media, tv, films, every thing displays you, I believe it may be very obscure how demeaning, how erasing it isn’t to ever see your self mirrored again, and the way that results in these internalized emotions of inferiority,” Hannah-Jones, a journalist specializing in civil rights and racial injustice for “The New York Occasions Journal,” founding father of the Pulitzer Prize-winning “1619 Mission,” and Swaby admirer defined within the exhibition catalog.

Artworks from Gio Swaby’s “Fairly Fairly” collection on view throughout “Gio Swaby: Contemporary Up” on the Museum … [+]

Museum of Advantageous Arts, St. Petersburg

“After I give it some thought on a private stage, there’s a journey that I’ve come by way of of studying to like myself,” Swaby admits. “I believe I’ll all the time be on this journey of unlearning and relearning. I’ve internalized a lot of what I now acknowledge as a perpetuation of white supremacy and changed it with private practices which might be rooted in anti-colonialism, love and care.”

Swaby doesn’t conceal from the actual fact her work has explicitly been created for Black girls and ladies. Not that everybody can’t get pleasure from it, however this work is unabashedly by, for and about Black girls and ladies.

“I wished to create an area the place we may see ourselves mirrored in a second of pleasure, celebrated with out expectations, with out linked stereotypes,” she says.

In fact, Swaby takes membership in that group as properly, and as has typically been mentioned, an individual can’t take care of others with out caring for themselves. Swaby’s artwork does that.

“I see (my artmaking) as part of the method of therapeutic from the traumas I’ve endured all through my life. I do that work in order that I do know that it’s potential,” Swaby says within the guide. “I do know that’s odd to say as a result of I’m the individual doing it, but it surely’s nonetheless a reminder to me that it’s potential to attain the best issues that I aspire to despite a system that’s constructed in order that I might not ever come near reaching them.”

Portraiture as activism.

In Her Personal Phrases

A revealing characteristic of the “Contemporary Up” exhibition has Swaby introducing every collection on show by way of a private, written introduction.

Prefacing “My Palms are Clear,” she writes:

“I don’t care in case your ‘fingers are clear,’ as a result of what you’re actually asking is that I sacrifice my private consolation to fulfill your curiosity. It isn’t an harmless request. You don’t understand how. You aren’t certified. You’ll actually disturb the magical forces that maintain my fro or my braids or my flat twists in all their glory. Caring for my hair is an act of affection initiated and mediated by contact. Don’t disrupt, disrespect or dishonor this sacred area.”

“Gio Swaby: Contemporary Up” set up view.

Museum of Advantageous Arts, St. Petersburg

Black girls’s hair performs a central position in Swaby’s artmaking. Her “New Development” collection serves as an ode to Black hair.

“This collection honors the activation of ancestral data by way of the act of hair care,” wall textual content reads. “I see my hair as a bodily connection to my lineage; it provides me a glimpse into the existence of my ancestors whose private histories had been buried in colonial retellings. I see caring for my hair as a pathway to reconnection. A pervasive colonial normal of magnificence can overwhelm us with trauma and disgrace linked to our hair. This collection is a means for me to contribute to the continued efforts of repositioning Black hair as an attractive extension of ourselves to be cared for love and held within the highest regard.”

Swaby, refreshingly, makes no effort to be coy about her art work and its motivations. Whereas advanced, it isn’t mysterious. Deeply significant and crystal clear. In these methods she opens her work for appreciation to a wider viewers among the many common public, an viewers partially mirrored in her portraits, an viewers museums have traditionally failed to draw–or attempt to. Or need to.

“Gio Swaby: Contemporary Up” could be seen in St. Petersburg by way of October 9, 2022, adopted by stops on the Artwork Institute of Chicago, April 8 to July 3, 2023, and the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, MA August to November 2023.