This particular report is the primary of two components. Learn half 2 right here.

The 764-page report minces no phrases in regards to the inequality rife all through medical care: “Racial and ethnic minorities expertise a decrease high quality of well being providers, and are much less more likely to obtain even routine medical procedures than are white People.”

These phrases might need been written lately, amid a pandemic that has disproportionately sickened and killed individuals of colour. In truth, they had been written twenty years in the past.

commercial

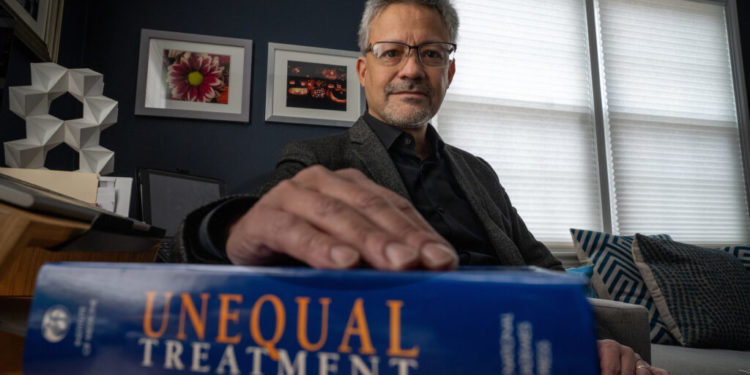

“Unequal Treatment” was the primary main report back to level to longstanding systemic racism — not poverty, lack of entry to well being care, or different social components — as a serious cause for the nation’s deeply entrenched well being disparities. The authors, a blue-ribbon panel of the Nationwide Academies’ Institute of Drugs, hoped their work would kickstart a nationwide dialogue and result in much-needed change.

On the time, the report despatched shock waves by means of drugs. David R. Williams, a committee member and well being fairness scholar then on the College of Michigan, known as the findings “a wake-up name for each healthcare skilled.” There have been entrance web page headlines, pointed editorials, and several other congressional hearings. “For us as individuals of colour, we’re simply not going to be sick and drained anymore,” Donna Marie Christensen, a doctor and congresswoman representing the U.S. Virgin Islands, stated at an April 2002 listening to held a number of weeks after the report’s launch to push the Division of Well being and Human Providers to do a greater job.

However at present, the disparities — poorer outcomes and better dying charges for almost each medical situation the panel examined — and the structural racism underlying them, stay. That grim fact has been made startlingly clear by each the pandemic and by statistics that present Black People proceed to die up to five years earlier than those that are white.

commercial

“There hasn’t been lots of progress in 20 years,” stated Brian Smedley, a well being fairness and coverage researcher with the City Institute who served because the report’s lead editor. “We’re nonetheless largely seeing what some would name medical apartheid.”

The Facilities for Illness Management and Prevention estimated that in 2019, some 70,000 Black People — almost 200 per day — died prematurely, many from power situations like coronary heart illness that would have been higher handled. To Williams, the dying toll is nothing lower than the equal of a completely loaded jumbo jet falling out of the sky every day.

“Are you able to think about?” Williams, now on the Harvard T.H. Chan Faculty of Public Well being, requested lately. “Congress can be holding hearings and transferring heaven and earth. … Why are we so laid again about this lack of life on an unprecedented scale?”

Why, certainly? And why has there not been extra work, laws, and progress when the problems laid naked by Covid — poorer care and better dying charges for individuals of colour — had been established so clearly and with such precision twenty years in the past? Why had been so few of the report’s 21 detailed suggestions put into place? To look at these questions, STAT spoke with the individuals who created the landmark report about why the disparities they highlighted have remained so intractable.

The explanations they level to are myriad: Our nationwide discomfort with confronting the long-taboo subject of race stays a roadblock, as does widespread denial amongst well being care suppliers that they could be a part of the issue. Different points embrace complacency; an absence of constant political will to eradicate inequities; well being disparities work being elbowed out of the best way when different priorities come up; a fragmented well being care system that isn’t amenable to common options; and a dearth of high quality racial and ethnic information wanted to trace whether or not efforts to finish disparities are working.

Whereas the report’s anniversary raises deeply unsettling questions on why so little progress has been made previously 20 years, the query now’s whether or not the highlight aimed on racism in drugs by the pandemic will lastly spark lasting change, or whether or not this second of alternative, too, will cross.

A completely different epidemic, AIDS, was sweeping the nation when the problem of well being disparities first reached the nationwide stage in 1985. That yr, HHS, underneath the management of Margaret Heckler, launched a complete nationwide examine demonstrating that folks from many racial and ethnic teams had greater burdens of illness and decrease life expectations than white People. Often known as the Heckler Report, the doc was a wake-up name. However a lot of the follow-up to the report sidestepped the problem of racism, focusing as an alternative on whether or not the disparities had been brought on by components akin to gaps in revenue, schooling, or insurance coverage protection.

Some 15 years later, Congress directed the Nationwide Academies to look particularly at whether or not racism, bias, discrimination, and stereotyping additionally performed a task. “We had an essential alternative to see if race and racism mattered,” stated Smedley. “And it mattered.”

The report confirmed — in exacting element and with mountains of proof — that folks of colour had been much less more likely to obtain the medical care and procedures they wanted even when controlling for components like insurance coverage standing. It confirmed that Black and Hispanic sufferers tended to obtain lower-quality take care of a variety of ailments, together with most cancers, coronary heart illness, HIV/AIDS, and diabetes, and that disparities had been discovered even when scientific components like comorbidities, age, and severity of illness had been taken into consideration. The disparities had been discovered throughout a variety of scientific settings, together with public, non-public, and instructing hospitals, and had been tied to worse outcomes for sufferers.

“Regardless of regular enchancment within the total well being of the U.S. inhabitants, racial and ethnic minorities, with few exceptions, expertise greater charges of morbidity and mortality than non-minorities,” the report stated, calling the more serious medical outcomes “unacceptable.”

What got here as a shock on the time, even to some IOM committee members, was the discovering that unconscious bias and stereotyping amongst medical doctors, nurses, and different well being care suppliers contributed to the poorer care sufferers of colour acquired. “Analysis means that healthcare suppliers’ diagnostic and remedy choices, in addition to their emotions about sufferers, are influenced by sufferers’ race or ethnicity,” the report stated. The authors additionally cited the shortage of physicians of colour and language translation providers, a dearth of medical services in some low-income neighborhoods, and a shift to managed care in government-run well being applications as examples of systemic racism.

In well being care circles, responses to the report fell largely into two camps, Smedley stated. Some knew the disparities had been actual as a result of that they had lived them or knew the medical literature, whereas others had been outraged by the notion that medical doctors is likely to be biased. “Folks had been shocked. They had been aghast,” stated Smedley. “Folks say, ‘Sure, well being care inequities are actual, however not in my apply.’ I hear that to today.”

“A part of what we’re combating within the U.S. is we’re unwilling to be taught our historical past and unwilling to simply accept our complicity on the subject of racial inequality,” he added.

“There hasn’t been lots of progress in 20 years. We’re nonetheless largely seeing what some would name medical apartheid.”

Brian Smedley, well being fairness and coverage researcher and the report’s lead editor

Alan R. Nelson, a retired Utah doctor and former president of the American Medical Affiliation, chaired the committee, a task he describes as a spotlight of his profession. He credit the report with elevating consciousness amongst medical organizations. “All of them wakened and stated, ‘This can be a drawback and we have to do one thing about it,’” he stated.

However doing one thing about disparities is difficult, he stated, as a result of there are such a lot of contributing components. And denial stays widespread. “When you surveyed 1,000 American medical doctors and requested, ‘Do you apply in a approach that contributes to well being care disparities?’ they’ll all say no, as a result of they actually imagine they don’t contribute to well being care disparities,” Nelson stated. “It’s an enormous drawback.”

In a single echo of how little desirous about racism has modified amongst well being care suppliers, a Journal of the American Medical Affiliation podcast host claimed final yr that medical doctors can’t be racist.

Twenty years in the past, open discussions of race and use of the time period racism had been deeply uncomfortable for a lot of in drugs and science. Williams stated a reviewer as soon as advised him outright the time period didn’t belong in a scientific paper.

On one hand, there’s been progress: Racism is now extra generally utilized in each papers and discussions and is more and more seen as a legitimate area of scientific study. However well being fairness students say they now worry a cultural backlash spawned by extra open discussions of race. Not too long ago, two dozen white nationalists protested outdoors a Boston hospital towards a pilot challenge aiming to eradicate racial disparities in cardiac care. The backlash contains calls to ban the dialogue and instructing of crucial race concept on faculty campuses and opposition to exposing medical students to antiracist concepts.

“It’s truthfully chilling me to the bone. I’m so involved about this motion,” Paula Lantz, a professor of public coverage and well being administration coverage on the College of Michigan, stated at a current well being fairness summit held by the Hastings Heart. “There will be no progress towards well being fairness with out the naming, framing, and dismantling of structural racism.”

The Latina daughter of a migrant farm employee from Fresno, Calif., Carolina Reyes had grown up by no means seeing physicians who seemed like her. Now a specialist in high-risk maternal-fetal drugs in Sacramento who teaches on the College of California, Davis, Reyes helped create the report whereas a younger college member at UCLA.

Reyes stated the report broke lots of new floor. “It was the start of the popularity that well being care suppliers performed a task, that by stereotyping and bringing in their very own biases, they contributed to unequal remedy.”

There was some enchancment lately, she stated. Mandated by Congress, the federal authorities now stories on well being care high quality and disparities skilled by racial and ethnic teams, and plenty of clinics and hospitals supply translation providers to non-English audio system. Reyes stays wistful, although.

“It’s wonderful. It’s 20 years later and it seems like we haven’t moved the dial very a lot,” Reyes advised STAT. “On the time, there was a stage of pleasure about what we might change, however with the whole lot that’s new, it will possibly wane.”

“Wanting again, there was a sense of complacency about disparities, that they had been there as a result of individuals have completely different lives,” she stated, “as an alternative of claiming, ‘Wow, that is unjust.’”

Complacency about well being disparities has been a recurring drawback. At a 2010 workshop held by the Nationwide Academies to evaluate how a lot progress had been made since 2000, Smedley and Williams reported that the problem had gained much less traction than they’d hoped as a result of different nationwide points, such because the financial downturn of the time, had taken heart stage. In addition they famous that the election of Barack Obama could have damage the trigger; individuals had been extra simply in a position to inform themselves racism didn’t exist in a rustic that had elected a Black president. At present, some worry that the widespread urge to return to a post-pandemic “regular” could permit consideration on well being fairness points to recede.

Many who work within the discipline of well being fairness wish to say that the lengthy arc of historical past finally bends towards justice. However because it bends, it will possibly additionally wobble: The story of well being fairness within the U.S. is a fragile one, filled with progress and retrenchment. “By my rely, we’re in our fourth nice awakening for well being fairness,” stated Daniel Dawes, a well being coverage knowledgeable who wrote “The Political Determinants of Well being” and leads the Satcher Well being Management Institute on the Morehouse Faculty of Drugs.

These awakenings, he advised STAT, embrace Abraham Lincoln’s coverage to offer well being care to newly freed individuals and poor white individuals; desegregation of hospitals within the Nineteen Sixties on account of Medicare and Medicaid laws; passage of the Reasonably priced Care Act and the publication of main stories on well being disparities akin to “Unequal Remedy” this century; and, in fact, the present second.

The large query, Dawes stated, is whether or not this time, there’s a political and nationwide will to lastly finish these disparities. Doing so, notes David Satcher, who was U.S. surgeon common when the report was being produced, would save much more lives every year than drugs’s boldest high-tech interventions.

Different authors of “Unequal Remedy” share the frustration that extra hasn’t been carried out. “It’s not as if we don’t know what to do,” stated Risa J. Lavizzo-Mourey, a former president and CEO of the Robert Wooden Johnson Basis and professor emerita on the College of Pennsylvania who was one of many IOM committee’s vice chairs.

One drawback, Lavizzo-Mourey advised STAT, is that the report’s almost two dozen suggestions had been embraced in some quarters, however by no means taken to scale. There was no coordinated effort to counter the structural racism the report uncovered, she stated, including that such efforts stay difficult as a result of the nation’s well being care system is so fragmented. “You’ve acquired the federal authorities, the DOD [Department of Defense], the VA, and Medicare, then you could have 50 states that weigh in,” she stated. “That is the issue with altering something within the well being care system. It’s not a system.”

The Reasonably priced Care Act has elevated entry to well being care to many individuals of colour, Lavizzo-Mourey famous. Tons of of cities and counties, and even the CDC, have called racism a public health issue. The federal government’s Company for Healthcare Analysis and High quality points a report on health disparities every year. And the Nationwide Institutes of Well being upgraded its Heart for Minority Well being and Well being Disparities from a middle right into a full-fledged institute.

However that progress has been spotty. For instance, whereas the gathering of racial and ethnic information to trace disparities has improved since 2002, it’s still largely a mess.

On the time the report was written, most work on well being disparities targeted on Black sufferers; there was a lot much less give attention to these from different races and ethnicities. “Native People and Alaskan Natives went into the ‘different’ class. We had been misplaced to a sure extent,” stated Jennie Joe, a medical anthropologist and professor emerita of household and group drugs who lately got here out of retirement to function interim director of the Wassaja Carlos Montezuma Heart for Native American Well being on the College of Arizona.

“The information we chosen (for the report) jogged my memory about what was lacking,” she stated. “The information wasn’t giving us the entire image — and a few of these issues nonetheless exist.” Underreporting of Covid information in Native communities, for instance, made it onerous for tribal leaders to reply successfully to the pandemic, she stated.

Joe stated her journeys to Washington to work on the report all the time stirred lots of optimism. “There was hope after we all acquired collectively and talked, however whenever you went again to your own home setting, you’d be overwhelmed,” she stated. “Sort 2 diabetes in children, childhood weight problems. Many people noticed the urgency and wish in our personal worlds.”

“I actually wish to suppose we made progress, however I’m all the time reminded that we haven’t — particularly with the pandemic,” stated Joe, who grew up within the Navajo Nation, which skilled a devastating dying toll from Covid. “All of the issues that had been hidden are actually seen.”

Coming tomorrow: The nation hasn’t made a lot progress on ending well being disparities. These leaders solid forward anyway.

That is a part of a collection of articles exploring racism in well being and drugs that’s funded by a grant from the Commonwealth Fund.

In-form Havertz scores again as Chelsea leave it late to beat Newcastle

In-form Havertz scores again as Chelsea leave it late to beat Newcastle