Conscious of the contexts by which his works are produced, artist and social activist Cian Dayrit advocates for the inclusion of the narratives of underrepresented populations, taking part in his half as one ingredient of a bigger collective resistance. I sit down with him to debate how he defends the rights of marginalized and disenfranchised populations.

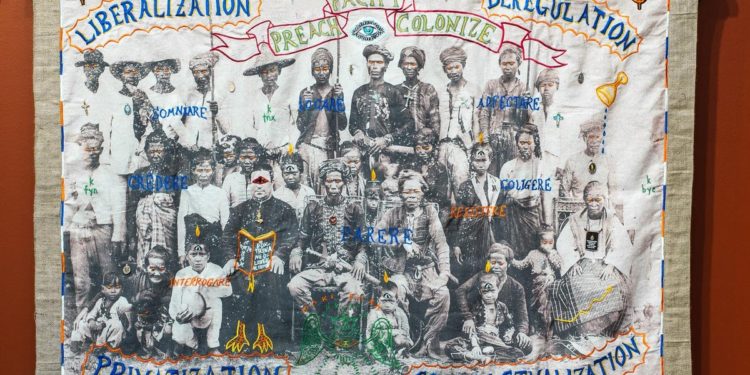

Cian Dayrit, NL Doctrine, 2019, objects, embroidery and digital print on textile, 51 x 64 inches, … [+]

Photograph Katarzyna Perlak

You have been born in Manila in 1989. Inform me about your mother and father, your childhood, if any of your loved ones members have been artists, how and once you turned enthusiastic about artwork, and once you knew you needed to be an artist.

A middle-class Catholic household within the metropolis. Comparatively comfy in a comparatively uncomfortable society the place privilege is a foreign money. I don’t keep in mind precisely how I got here to be an artist. There have been a number of elements, considered one of which was recognizing that artwork, or cultural work in a broader sense, was a possibility to interact in direct motion to study and tackle the contradictions of our present social order, which in fact I used to be but to totally perceive. I keep in mind watching some movies of a bloodbath of farmers protesting in 2004. I used to be completely destroyed by the concept such injustice has been occurring simply outdoors my comfy city bubble.

Why have you ever chosen to give attention to notions of energy and id as represented and reproduced in monuments, museums and maps?

Rising up, I used to be all the time fascinated by how these objects and locations commanded a lot energy by dictating how civilization is perceived. I used to be equally entranced and horrified by how the individuals who made this stuff might impose their perspective onto everybody else. As a response to the speedy circumstances which I used to be slowly recognizing, I needed to problem the views that someway monopolized the framing of historical past and heritage. Activism taught me that by studying from and placing to the fore the narratives of the intentionally silenced, marginalized sectors, social justice will be realized. By subverting the language of those establishments, I felt that I used to be filling within the gaps and democratizing the capabilities of narrative.

Cian Dayrit, Hiyaw ng Tingga, Asukal at Dugo, 2019, acrylic and collage on wooden, 96 x 96 inches, … [+]

Photograph courtesy of Cian Dayrit

How has the colonial historical past of the Philippines knowledgeable your work?

The colonial histories of the Philippines and different nations are pure departure factors in discussing present struggles. Colonialism by no means ended; it solely developed into up to date iterations of oppression and exploitation on a number of ranges.

Inform me about your time spent with indigenous peoples, peasants, the city poor and refugees, and your map-drawing workshops. What did you study from these communities? Why are you interested by defending the marginalized and disenfranchised, notably populations who’ve been dispossessed of their ancestral land?

The historical past of the Philippines is a historical past of wrestle between the ruling courses and the broad lots who’re marginalized and systemically oppressed. On this context, one has to take a facet. By remaining impartial, you’re naturally siding with the oppressive system. Peasants, employees, the city poor and ethno-linguistic minorities all bear the brunt of centuries of abuse. We have to attempt to perceive the buildings by which tradition, economics and politics perform. My follow is activated by solidarity within the struggles of oppressed populations.